- Plain Sight Productions

- Posts

- Destined for Glory

Destined for Glory

free will: myth or fact?

“By predestination we mean the eternal decree of God, by which he determined with Himself whatever he wished to happen with regard to every man. All are not created on equal terms, but some are preordained to eternal life, others to eternal damnation; and, accordingly, as each has been created for one or other of these ends, we say that he has been predestined to life or to death.”

Among a host of other topics, Catholics and Protestants unsurprisingly disagree about predestination. Just as unsurprising is that Protestants themselves disagree about predestination.

Those who hold to Calvin’s view (or at least something close) on predestination typically self-identify as Reformed, with the most popular type of reformed Protestant being Reformed Evangelicals.

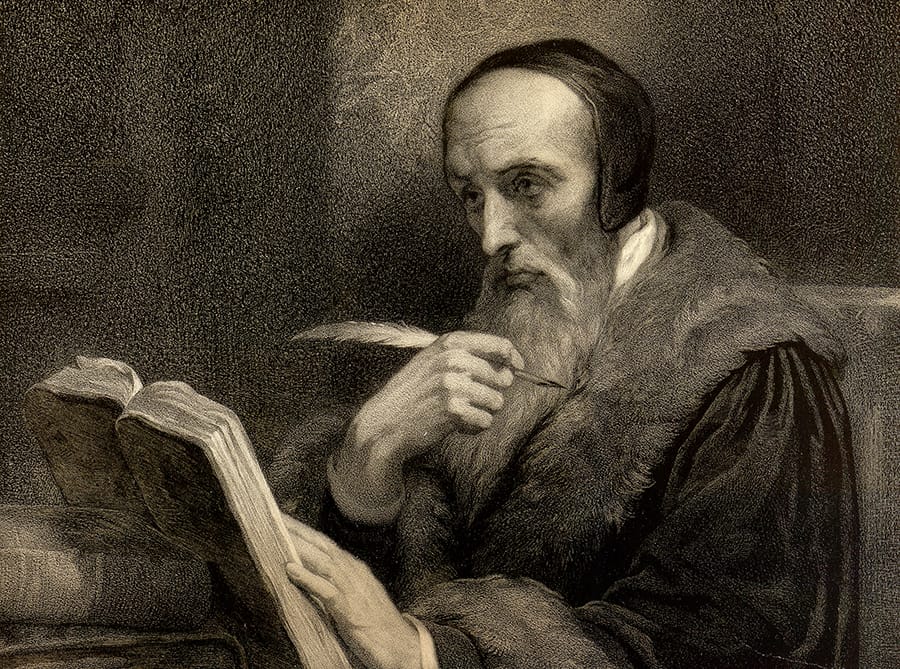

Before diving into what exactly it means to be a reformed Christian, we must first start with an overview of Calvin.

Born in 1509 in Noyon, France, Calvin grew up within the Catholic Church, educated for clerical life and formed by medieval scholastic categories he would later claim to reject. He was among the second generation of Reformers, as he was only eight years old when Martin Luther nailed his 95 Theses on the Wittenberg Church wall.

Although he and Luther are the two most notable revolutionaries, their styles couldn’t be more different. Luther was the bombastic orator that sought to persuade the room through verbal rhetoric.

Calvin, on the other hand, was the detailed and systematic writer trained in law who would rather sit at his desk diligently writing rather than give speeches.

great value thomas aquinas

Also, unlike the monastic Luther, Calvin was never ordained a priest.

By the time the Protestant Reformation began spreading across Europe, Calvin was already steeped in humanist thought and was convinced that the Church had obscured the Gospel beneath sacraments, hierarchy, and tradition.

His magnum opus, Institutes of the Christian Religion, was first published when he was just 26 years old.

The main themes included God’s sovereignty, man’s fallen nature, grace’s irresistibility, and most importantly, that salvation was not merely initiated by God but rather exhaustively determined by Him.

More specifically, God, from all eternity, chose who would be saved by bestowing a special and supernatural grace that would infallibly bring the “elect” to faith while passing over the “reprobate,” or non-elect. Thus, free will is simply the figment of our imagination, as there is nothing anyone can do to alter our final destination.

To Calvin, this was not cruelty but clarity. A God who depended on human cooperation was, in his view, no God at all. Human freedom could exist only as an instrument but never as a cause. Salvation was monergistic—not synergistic—as God alone acts, while man is acted upon.

When thinking of Calvinism, many people usually boil it down to the (in)famous five points, known as TULIP:

Total depravity

Unconditional election

Limited atonement

Irresistible grace

Perseverance of the saints

Interestingly enough, these five points of Calvinism didn’t come from Calvin but rather from a later council called the Synod of Dort in the 17th century, building off of Calvin’s work and responding to a different school of thought called Arminianism that pushed back on Calvinism’s determinism and lack of free will. Moreover, the TULIP acronym wasn’t used until the 20th century in English speaking countries.

Diving a bit deeper, Calvinists believe that God chooses these particular individuals not because he foresees they will believe or cooperate, but rather because He is showing mercy to them. With regard to the reprobate, skipping over them isn’t necessarily unjust because justice has to do with what is owed, and salvation is owed to none. More specifically, God does not infuse sin or force sin onto the reprobates but rather withholds the grace that would have saved them.

As Catholics, we can simply shake our heads at the idea of predestination and thank God that it doesn’t exist.

Right?

Wrong.

What if I told you predestination is actually dogmatically taught by the Catholic Church?

i know, i know, just hear me out

Now, to be clear, the idea that God actively selects who will be saved and also actively selects who will not is a heretical position.

To start off, when Catholics discuss predestination, it references God’s eternal plan to bring us to salvation by bestowing the graces needed to arrive there. The overarching emphasis is that God is the first cause in our salvific plan.

The main scriptural foundation for predestination is in Romans 8:

“We know that all things work for good for those who love God, who are called according to his purpose. For those he foreknew he also predestined to be conformed to the image of his Son, so that he might be the firstborn among many brothers. And those he predestined he also called; and those he called he also justified; and those he justified he also glorified.”

So at the very least, we know that there is some sort of plan made by God in which He predestines some people for justification and glory.

Additionally, in 1 Timothy 2, it is clear that God wants all of us to be saved:

“First of all, then, I ask that supplications, prayers, petitions, and thanksgivings be offered for everyone, for kings and for all in authority, that we may lead a quiet and tranquil life in all devotion and dignity. This is good and pleasing to God our savior, who wills everyone to be saved and to come to knowledge of the truth.

How is it that God seems to “choose” certain people to be saved but also wills everyone to be saved?

Similarly to Paul’s and James’s view on the relationship between faith and works, these two ideas seem to have friction at the very least and need to be reconciled in some way.

Let’s ask St. Thomas Aquinas to do the honors.

smartest man in the room.

The Thomistic explanation of predestination heavily focuses on the idea that man is completely incapable of reaching upwards, so to say, to God on his own and needs God to bestow grace on him first. This directly contradicts Pelagianism—an ancient heresy that teaches we can earn our salvation without the grace of God moving first.

“Predestination does not have its cause on the part of the predestined, but only on the part of God.”

“In adults, the beginning of justification must proceed from the prevenient grace of God… whereby, without any merits existing on their part, they are called.”

The idea of predestination is broader than simply the idea of election; it is about the ordering by God through the use of certain means to bring about a certain end through the preparation of gifts and graces to aid us in our ongoing theosis.

Using technical terms, God bestows everyone with sufficient grace, which is the grace given to us that provides us a chance to change our hearts and accept Him, allowing us to cooperate with His will. However, this grace can either be accepted or rejected.

The elect that are mentioned several times in Sacred Scripture are those who receive both sufficient grace and efficacious grace. The latter term describes the grace that infallibly moves people to cooperate with God’s will at every stage without trumping our free will. Thus, efficacious grace is 100% effective in achieving the desired result not through a form of determinism but through the supernatural ability to re-order our will to freely respond and cooperate with God’s will.

One very important note is that cooperation to His will does not cause the reception of efficacious grace but rather the opposite; receiving efficacious grace is the cause of our free cooperation. The reception of sufficient grace by all also affirms the idea that God wills all men to be saved, as it says in Timothy, as He gives everyone the opportunity to accept Him. The key to understanding this is to frame predestination and efficacious grace retrospectively rather than as a forward decree of damnation. Rather than saying those who do not receive efficacious grace are damned and those who do are saved, it is more accurate to say that those who are saved received efficacious grace, while those who are not saved freely and finally rejected the sufficient grace given to them.

Additionally, there is simultaneously no positive antecedent reprobation yet a positive consequent reprobation on the part of God. What this means is that God wills no one to hell before the consideration of merits (unlike the Calvinist position) but also wills the just punishment of the unrepentant sinner, fulfilling His role as the infinitely just God. From the Thomistic point of view, positive antecedent reprobation would include withholding sufficient grace from the non-elect, as this is the grace needed to be able to turn towards God. Coming back to Timothy, God’s will for all men to be saved is thus antecedent, as God will not consequently will the salvation of those who have rejected Him.

Thus we get the asymmetric order of salvation that Catholicism affirms: if we are saved, it is solely through God’s grace and mercy, but if we are lost, it is because we chose to reject Him through our free will. Specifically to Catholic doctrine, God does not cause any of us to either refuse baptism or commit mortal sin and not repent, but rather if we choose to do this, God permits us to do so.

This is known as single predestination, or the mysterious way in which God predestines certain individuals to glory yet does not predestine anyone to hell. This is juxtaposed by the Calvinist view of double predestination, in which God actively selects who will enter both heaven and hell, squashing the idea of free will. Long before Calvinism was even a thought in anyone’s mind, a regional council called the Council of Valence in the 9th century condemned double predestination:

“In regard to evil men, however, we believe that God foreknew their malice, because it is from them, but that He did not predestine it, because it is not from Him.”

Catholics do not affirm double predestination simply because it is not scriptural, as we see a predestination to glory mentioned in Sacred Scripture, but never any sort of predestination to hell. While it seems to be intuitive that the former would naturally gel with the latter, this highlights the necessity for the divine institution of the Church to be the sole interpreter of the Bible, as without it, the tendency to teach ideas that seem both logical and scriptural but are actually false is likely.

But as we all know, Luther, Calvin, and the other reformers disagreed with this assessment.

Interestingly, although he understood the doctrine well and acknowledged the scriptural foundations, Luther was not a fan of the seemingly constant dialogue surrounding predestination. In his eyes, he was wary about tangling too much with the predestination question because he observed a strong correlation between those who do so and those who come to the conclusion of “it doesn’t matter what I do since my eternal fate has already been sealed.”

He also denied the free will of both humans and angels.

The denial of human free will, specifically to choose God willingly, is not as controversial as denying angelic free will, as they are not tainted by the original sin of Adam. Therefore, under this view, the choice of some angels to reject God was not done willingly but was actively chosen by God, which contradicts the historical teaching of angels being created with both an intellect and a free will.

Coming back to Calvin, he notably admits that his view on predestination and the Early Church’s views do not see eye to eye. In fact, he essentially concedes that both Eastern and Western apostolic Churches disagree with his assessment on human free will:

“As if human nature were still in its integrity…the term free will has always been in use among the Latins (West), while the Greeks (East) were not ashamed to use a still more presumptuous term [self-determination], as if man had still full power in himself.

east and west unite 🤝

While the Church unites against the Calvinist position on predestination, there is some deliberation about what precisely is the correct view. While most Catholics that are aware of the teaching of predestination hold to the Thomistic view, there is another school of thought called Molinism that simultaneously affirms the asymmetrical nature of predestination while also slightly differing from Aquinas’s explanation. Since both teach predestination of the elect and God’s universal salvific will, Catholics can hold to either without falling into error.

The story behind Molinism will be covered.

Just not today.

All praise and glory be to God the Father through Jesus Christ in unity with the Holy Spirit for the birth of our Savior and the beginning of a new year.

Merry Christ-mass, Happy New Year to all, and God bless.

If you enjoyed this article, feel free to share with your family, co-workers, and friends and tell them to subscribe.

Thanks for reading and until next time.

Reply