- Plain Sight Productions

- Posts

- Vatican II (Part II)

Vatican II (Part II)

lex orandi, lex credendi

Picking up right where we left off after last week’s part I, to say that John XXIII had the complete overhaul of Catholic worship in mind when convening Vatican II is simply false. Even the modernization of the Church was not his main goal, although he had a few iterations in mind. The main two were to make a few minor liturgical tweaks—like having the readings said in vernacular—and to better catechize the faithful both on a local and universal level.

He eventually passed away during the council in 1963.

It was a tough year for Catholic leadership in 1963 to say the least.

the only respectable Catholic president #rip

Pope Paul VI succeeded him, and he was known to be more open to liturgical change, despite maintaining a strict conservatism when it came to doctrine. During his pontificate, he affirmed prohibition of contraception through Humanae Vitae in 1968 and upheld clerical celibacy.

With regards to liturgical changes, Paul VI designated Fr. Annibale Bugnini to spearhead the Consilium, the group in charge of implementing the reforms. Bugnini, known to be a liturgical reformist, had a lot of space to work with due to the vague language in the documents.

Many Vatican II critics label the ambiguity in the language as intentional so that the reformers would be able to alter the liturgy without directly contradicting the documents.

After all, what does ensuring that the liturgy has “noble simplicity” and “active participation” actually look like?

Bugnini was not the only one who desired change within the Church. There was a silent movement occurring underground in Catholic academia that seemed to be ideologically opposed to Catholic traditionalism.

Among the ideas circulating in these circles was a desire to “return” to a simpler form of liturgy, one that more closely modeled the early Church and allegedly emphasized the communal dimension of the Mass over its sacrificial character.

Many other ideas were far more nefarious.

As shocking as it may seem, here are some of the claims made by actual Catholic priests or theologians:

the Virgin birth was not a literal miracle but rather a “mythic expression of Jesus’s uniqueness”

Jesus Christ did not physically rise, but rather the disciples had “experiences of meaning”

the Eucharist is a symbol of community, not a supernatural transformation

miracles like walking on water, multiplying loaves, healing miracles, and more didn’t actually happen

traditional angelology and demonology are false

Now, the main reason for including these horrific denials of our Christian faith is to point out the reality that there were many bad actors in this story. In fact, with this type of evidence, the idea that individuals from groups fundamentally opposed to the Church—like Freemasons—infiltrated the Church in an attempt to destroy it doesn’t sound so ludicrous anymore.

More specifically, many believe that Bugnini himself was a Freemason. In 1975, a Dominican priest discovered a briefcase in a Vatican conference room that seemingly belonged to Bugnini. The materials included documents that were addressed to “Brother Bugnini” with signatures and place of origin that trace back to dignitaries of secret societies in Rome. According to some sources, he allegedly had joined the Masonic lodge on the feast of St. George in April of 1963. To be clear, the Church has never officially confirmed nor denied this, so it remains just a theory. However, the theory itself does fit the timeline, as it was around this time that Bugnini was essentially exiled to Iran, becoming the country’s nuncio, or ambassador–a clear demotion.

Coming back to the Consilium, the most notable work it published was the 1969 Missal, known as the Novus Ordo Missae. The new Missal was the main driver in overhauling the Old Rite to the one we have today: nearly exclusive use of vernacular, reception of communion on the hand, the shift away from ad orientum posture, and the de-emphasis of the sacrificial nature of the Mass.

For an entire generation of Catholics, the way in which they worshipped—undoubtedly one of the most important aspects of the faith—had essentially disappeared overnight. Those who had been longing for change in the Church were obviously elated. On the flip side, the rest of the faithful were shocked. It’s safe to say that many people are drawn to the Catholic faith because it is our civilization’s immovable and immutable rock, remaining sturdy despite the rest of the world constantly shifting. Although nothing about the Church’s actual doctrine changed, many felt as if the Church had given in to the pressure of the world and abandoned the tradition that the Church held onto for so long. For many, this was enough to doubt the validity of the Church and sadly, many left.

While most of the new versions of the Mass during the early 1970s still maintained the solemn feel of worship, the spirit of change that enveloped the Church gave the green light to these bad actors discussed previously to show their true colors.

Some Masses during this time were utterly profaned, as a handful of them were themed around secular movements like social and environmental justice, with some even referencing popular entertainment culture like Sesame Street and Star Wars.

Don’t even get me started on the clown Masses.

While it’s obvious Sesame Street and clown Masses are sacrilege, we’ll dive a bit deeper on the less controversial changes of the Novus Ordo and why they matter.

Reception of Communion:

We’ll start with the difference between receiving the Eucharist on the tongue while kneeling and receiving on the hand. Right off the bat, without getting into history, theology, or Sacred Scripture, which one demonstrates the idea that we are mysteriously receiving God in the flesh in a humble way, grateful to receive such a precious gift? If we were to ask an intellectually honest agnostic or anyone outside of the Church for that matter, it’s clear which would be selected.

Interestingly enough, revolutionaries like Protestant reformer John Calvin rejected kneeling and receiving on the tongue, promoting communion in the hand to emphasize the Eucharist as a symbolic commemoration and communal meal, rather than an act of adoration centered on Christ’s Real Presence.

With this in mind, many Christians will reference the fact that the earliest Christians received communion on the hand. While this is true in certain areas, there are two things that must be kept in mind. Firstly, by the 9th century, reception on the tongue became the norm in both the East and the West, as the Church gradually concluded that reception on the tongue better depicted the reverence needed to receive the actual body and blood of Christ. Also, even when the earliest Christians did receive in the Eucharist in hand, it was placed in one’s right hand (symbolizing Jesus at the right hand of the Father) and scooped up by the tongue directly as a way of communicating that we are not feeding ourselves spiritually but rather the recipients of the Christ-instituted sacrament.

Ad Orientem:

Many people likely think: does it really matter which way the priest faces?

The answer is yes.

The way in which the priest faces is not some arbitrary decision but rather communicates a real message on the Mass’s purpose.

Before discussing the Mass’s sacrificial nature, the priest has historically faced ad orientem, meaning towards the East, in the symbolic direction we expect to see the Lord return for His second coming. More importantly, the posture is not put in place to have his back facing away from the people per se, but rather to face God as the priest addresses Him on our behalf.

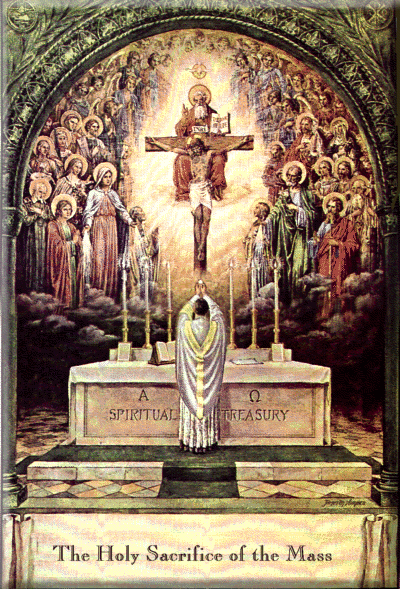

To start off, the Mass is a sacrifice. When was the last time you heard someone say that? If you consume online Catholic content, you’ve probably heard that recently. However, during most people’s actual Catechesis coming from the Church, this idea seems to get lost or is intentionally withheld. One of the many changes due to the “spirit” of Vatican II is that the emphasis of the Mass changed from participation in Christ’s sacrifice on Calvary to a communal meal.

Throughout the history of the Church, Mass has always been described as a place in which time collapses and we witness Christ’s sacrifice, thus receiving the graces flowing from the Cross.

With this in mind, the priest facing away from the people and towards the tabernacle during consecration perfectly depicts what is occurring: the priest, acting in persona Christi, represents Christ offering Himself (the Eucharist) up as a sacrifice to the Father with the Church militant (Christians on Earth) and Church triumphant (Christians in heaven) witnessing the canon event in awe.

“The sacrifice of Christians is the Body of Christ, offered in the mystery of the Eucharist…Christ is both the priest, offering sacrifice, and the sacrifice itself.”

Gregorian chant:

While contemporary music that praises the name of Jesus Christ is all good and well, as Catholics we believe that it shouldn’t take precedence over Gregorian chant in the context of liturgy.

Firstly, Gregorian chant—just from an aesthetic point of view—far surpasses any contemporary music in terms of the effects it has on the soul. There is something that is extremely calming about the ancient melodies that simply can’t be outdone. While a bit hard to explain, the use of Gregorian chant during Mass provides a level of sanctity that modern music just can’t match. When hearing Gregorian chant at Mass, one genuinely feels like they are participating in the clash between heaven and earth. Not only is Gregorian chant holy and beautiful, but it is universal, transcending time, genres, regions, and more. Because of this, the Church has long maintained that Gregorian chant and the liturgy go hand in hand, with Vatican II’s documents upholding this:

SC (Sacrosanctum Concilium)116: “The Church acknowledges Gregorian chant as specially suited to the Roman liturgy. Therefore, other things being equal, it should be given pride of place in liturgical services.”

SC 114: Sacred music is not an optional decoration but an integral part of the liturgy.

Latin as the language of the Mass:

When it comes to Latin being the Mass’s language, it goes far beyond the idea that Latin sounds way cooler than any other language, although that undeniably is a fact. It is also deeper than the idea that the Church’s history is deeply intertwined with the Roman empire, thus becoming the language of the Church after Constantine helped the religion emerge from underground. The most vital reason why Latin is used in Mass is because it’s a sacred language. According to many theologians and Church Fathers, Latin became sanctified at the moment in which the “INRI” label was placed on the cross, reading "Iesus Nazarenus, Rex Iudaeorum,” or Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews.

ave christus rex #hebrewsmad

At that very moment, Latin became directly attached to the physical instrument that granted us the salvation we are unworthy of.

There’s also the reality of Latin serving as a symbolic veil that prevents the faithful from fully grasping what is going on. While the Protestant ethos abhors this, it is still intuitive nonetheless. It almost makes sense to not be able to grasp the miraculous and mystical experience that worshipping God really is. After all, the fullness of God’s essence is impossible to fully understand in this life.

Synthesizing all of this together, one has sufficient evidence to claim that there could be a causal relationship between the reforms of Vatican II and the decline in Catholic religiosity starting in the 1960s.

Perhaps the absence of Gregorian chant made Mass feel less mystical and less of something that is the highest form of worship.

Perhaps the change in the reception of communion inadvertently decreased reverence for the Eucharist, leading many to slowly doubt the Real Presence of Christ.

Perhaps the move to versus populum drew people away from the sacrificial nature of Mass, ignoring a major function of the liturgy, potentially creating a ripple effect of unbelief.

The changes didn’t just stop there either.

The Eucharistic fast used to be from midnight but was reduced to three hours until finally settling on the one hour fast we’re used to.

Every Friday was a strict day of abstinence from meat before becoming optional as long as one engages in a substitute penance.

Ember and rogation days used to be roughly four times a year in which fasting and penitential observances were made in addition to processions.

Rosaries before Mass used to be commonplace; now, they’re a rarity.

Only priests and deacons used to distribute Communion and read readings before becoming accessible to lay people.

Whether these changes had a causal effect on the Church’s decline or not is up for debate.

What is not up for debate is that the Catholic faith in America did indeed experience a sharp decline.

number of US priests decreased from 59,000 to 34,000 (1965 to 2022)

Mass attendance decreased from 75% to 25-30% (late 1950s to now)

Catholic school enrollment decreased from 5.2 million to 1.7 million (early 1960s to 2019)

number of nuns decreased from 178,000 to 39,000 (1965 to 2022)

As previously mentioned, many Catholics—although none of the dogmas or doctrines of the Church had changed—felt as if something of a new religion had just been established.

“I am convinced that the crisis in the Church that we are experiencing today is to a large extent due to the disintegration of the liturgy…

When the liturgy is trivialized, faith becomes trivialized.”

Imagine one year, you arrive at Mass to see incense, altar rails, and Gregorian chants, and the next thing you know, you’re listening to a homily from a lay person.

This was the reality for some Catholics.

So, how did Pope Paul VI react?

By 1975, he knew that the Consilium was a mistake. That year, he dissolved the committee and abolished Bugnini’s position before sending him to Iran, as mentioned earlier.

But it was too late.

The “good ol’ days” were officially in the rearview mirror.

The Tridentine Rite was old news now.

Paul VI would eventually pass from this life to the next in 1978, and Albino Luciani was elected as his successor in August of 1978. Luciani greatly admired Pope John XXIII, who anointed him as a bishop, and Pope Paul VI, who anointed him a cardinal. He wanted to take on one of these names, but wasn’t sure which one to go with.

In an unprecedented move, he took on both of them, becoming Pope John Paul I.

His reign as sovereign of the Church lasted for just 33 days before passing away from an apparent heart attack.

Karol Wojtyla, a cardinal from Poland, would continue in his footsteps and take on the name Pope John Paul II. JPII and his successor Pope Benedict XVI were both liturgical conservatives and both acknowledged the validity of the Old Rite and the abuses that were prevalent in the aftermath of Vatican II.

“It is sometimes claimed that the reforms authorized by the Second Vatican Council have given rise to many abuses… We must admit that these have indeed occurred.”

“What happened after the Council was something else entirely: in place of the liturgy as a fruit of organic development came a fabricated liturgy.”

Both popes understood the fruitfulness of the old Mass and were sympathetic to those who were still drawn to it. During this time, although the Old Rite had never been officially abrogated, it was essentially prohibited. Priests who wanted to celebrate the Tridentine Mass needed special permission from their bishops, who would typically say no. Why exactly they would say no is a bit mysterious, but the most likely reason was a suspicion of spiritually schismatic behavior.

Despite Pope John Paul II urging the bishops to be generous in granting the old Mass in his 1988 Ecclesia Dei work, the real progress occurred in 2007 when Benedict XVI permitted priests to celebrate the TLM privately without permission from a bishop.

In a practical sense, this was the best Benedict XVI could do, as the idea of switching back to the Old Rite would be implementing a sort of liturgical whiplash that didn’t seem to be a good idea.

Which brings us to today.

Kind of.

Before continuing the tirade of how Vatican II “destroyed the reverent liturgy,” we must take a second to analyze the other side.

The first question we must ask is this: what percentage of the decline in Catholic religiosity can be explained by the broader secularization that was occurring in the 1960s? After all, this was the infamous decade of social upheaval that saw the civil rights movement, second-wave feminism, Roe v Wade, the sexual revolution, no fault divorce become prevalent, the move for a complete separation of Church and state, and more. Even if nothing about the Church changed, it is fair to say that there still would have been some sort of religious decline as a result.

Also, when analyzing causes and effects over time, we must take into account that the Church has been around for nearly 2000 years, so the 60 years that have passed since the council really hasn’t been very long. When discussing Vatican II, Bishop Barron alludes to the fact that although the Arian crisis was still alive and well 60 years after the First Council of Nicaea, we obviously can’t label the council as “a failure,” as we can now look at the history in totality and acknowledge that was nothing remotely close to a failure.

Another aspect to consider is that although the Catholic Church and Western civilization are inextricably tied together for eternity (hopefully), the Church is not a Western Church; it is a universal Church.

A unified, holy, universal, and apostolic Church to be exact.

So while the Church has been in decline in the West for a handful of decades, the Church has exploded in other areas of the world like Africa and parts of Asia.

This is undeniably good news.

While we can praise God for the growth in different parts of the world, it is fair to express concern about the West given that, in the words of comedian Shane Gillis, the Catholic Church “invented the Western world.”

But don’t look now because some are calling it a comeback.

the truth will prevail

Not only is the number of people coming into the Church increasing, but the number of serious, traditional Catholics seeking the Extraordinary Rite is increasing as well.

In theory, the TLM should be on the decline and be filled with the eldest members of society who are nostalgic and grasping to be reunited with the “good ol’ days” when Mass was celebrated the “way it should be.”

But in reality, it’s the opposite.

While many Novus Ordo Masses tend to have high proportions of elderly people, it’s the TLM’s that are filled to the brims with not just young people, but young couples with lots of children.

In an interesting paradox, the demographic theorized to feel alienated and disconnected with the Roman Rite is the same one who yearns for it most.

There are a few reasons for this.

The first obvious point is people, no matter which generation they are from, are drawn to beauty. And boy, is the Old Rite beautiful.

Additionally, the longing to be around those who take the faith seriously is a real desire for many young Catholics, and this is felt when attending TLM. While physical appearance during Mass isn’t everything, the stark contrast in the casual wear at NO Masses and the formal wear at TLM points to the general conclusion that TLM attendees are more likely to treat Mass as the most important event of the week rather than checking the box for their weekly obligation.

Also, most Gen Z’ers and millennials have grown up in a much more modernist world where they’ve been inundated with secular ideals from a very young age. While many will of course continue to embrace the secular “young person” lifestyle, a higher percentage than normal are beginning to reject these principles and instead seek for things more ancient, transcendent, and traditional, which perfectly describes the TLM.

In the same way that it’s comforting to know that the beliefs we hold as Catholics have historical continuity and trace back to the earliest Christians, there is also a comfort in knowing that the form of Mass being celebrated is the same as your predecessors.

Comfort in tradition: nothing is better.

Thanks be to Jesus Christ for the American Catholic Renaissance 2.0.

If you enjoyed this article, feel free to share with your family, co-workers, and friends and tell them to subscribe.

Thanks for reading and until next time.

Reply